Joe Mantello and an all-star cast take The Boys in the Band from stage to screen.

Joe Mantello and the outstanding cast of his Tony Award-winning 2018 revival of The Boys in the Band logged countless hours of work before they started translating the production to the screen. After weeks of rehearsals and months of nightly performances, the director and his ensemble — Jim Parsons, Zachary Quinto, Matt Bomer, Andrew Rannells, Charlie Carver, Robin de Jesús, Brian Hutchison, Michael Benjamin Washington, and Tuc Watkins — had come to feel in their bones the intricacies and interplay of the characters. “We weren’t really starting from scratch,” Mantello reflects.

Still, as the actors dove back into the roles they knew so well, they were met with a sense of discovery just as they had been each night onstage at the Booth Theatre in New York. “Doing the film, I felt like there was so much more,” Quinto says. “We had so much fun. It felt so informed, and it felt like it was a more tangible playground in the film world because that’s just the nature of the medium.”

An Off Broadway sensation when it premiered in 1968 — a year before New York’s Stonewall uprising — Mart Crowley’s landmark play tells the story of a group of gay men who gather one night to celebrate their friend Harold’s (Quinto) birthday. Michael (Parsons), the host of the soirée, is surprised when his college roommate Alan (Hutchison) unexpectedly turns up, and as the evening wears on, insecurities, jealousies, and rivalries begin to surface. When Michael insists that each man participate in an emotionally savage parlor game, tensions reach a boiling point.

That 1968 production was the first play centered on the lives of gay men to reach the mainstream. It became an immediate phenomenon and spawned a controversial 1970 cinematic adaptation directed by William Friedkin. With its wicked humor and lacerating insight, the new film, produced by Ryan Murphy, David Stone, and Ned Martel, remains faithful to Crowley’s revolutionary text. Yet the screenplay, credited to both the late playwright and Martel, concludes on a somewhat more hopeful note, suggesting, perhaps, a future in which the characters might come to find acceptance and love.

Mantello and the stars (minus Rannells) recently gathered for a roundtable conversation moderated by playwright Matthew López, author of The Whipping Man and the hit Broadway play The Inheritance, to chat about the screen adaptation and the ongoing relevance of Crowley’s work.

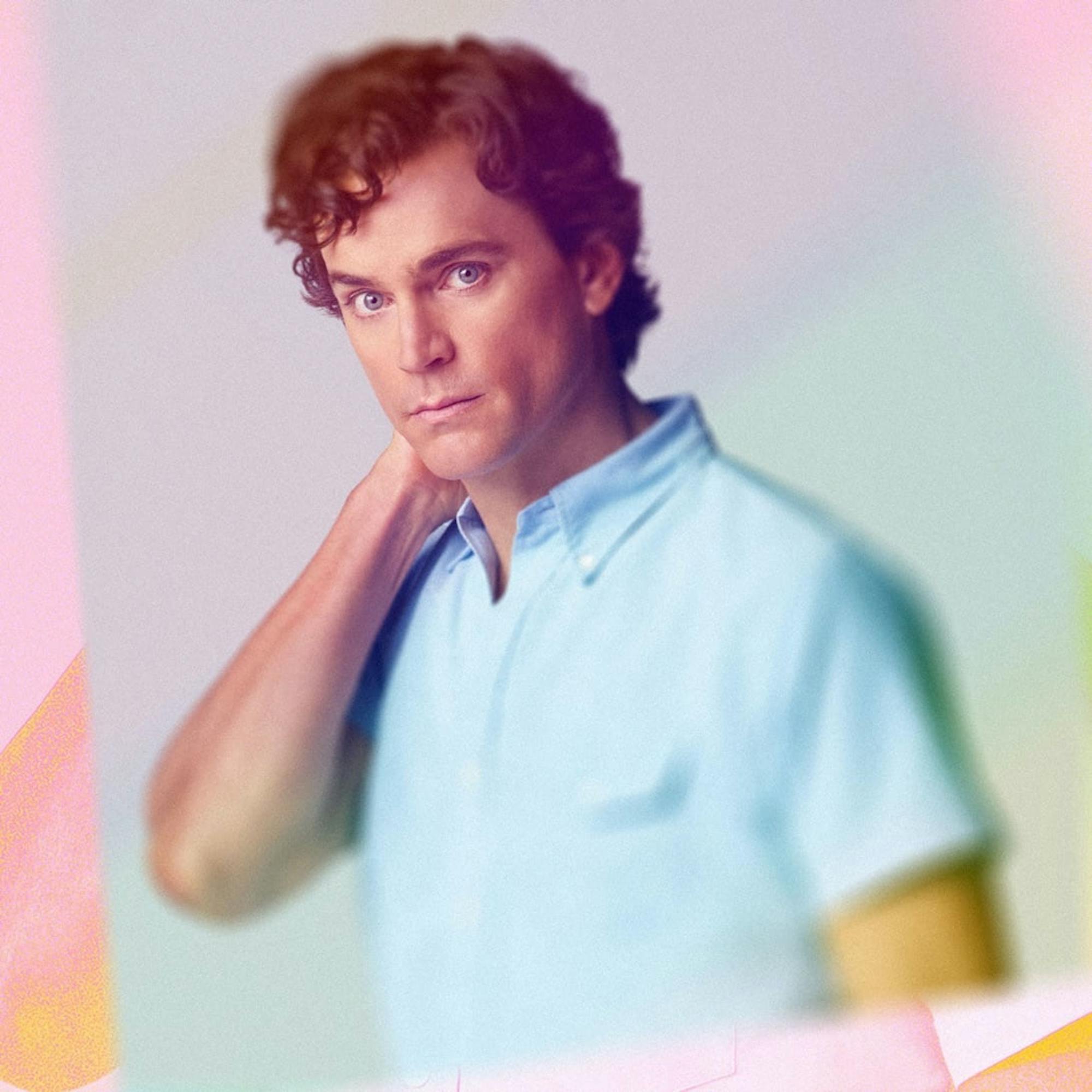

Joe Mantello

Photograph by Dave Krysl

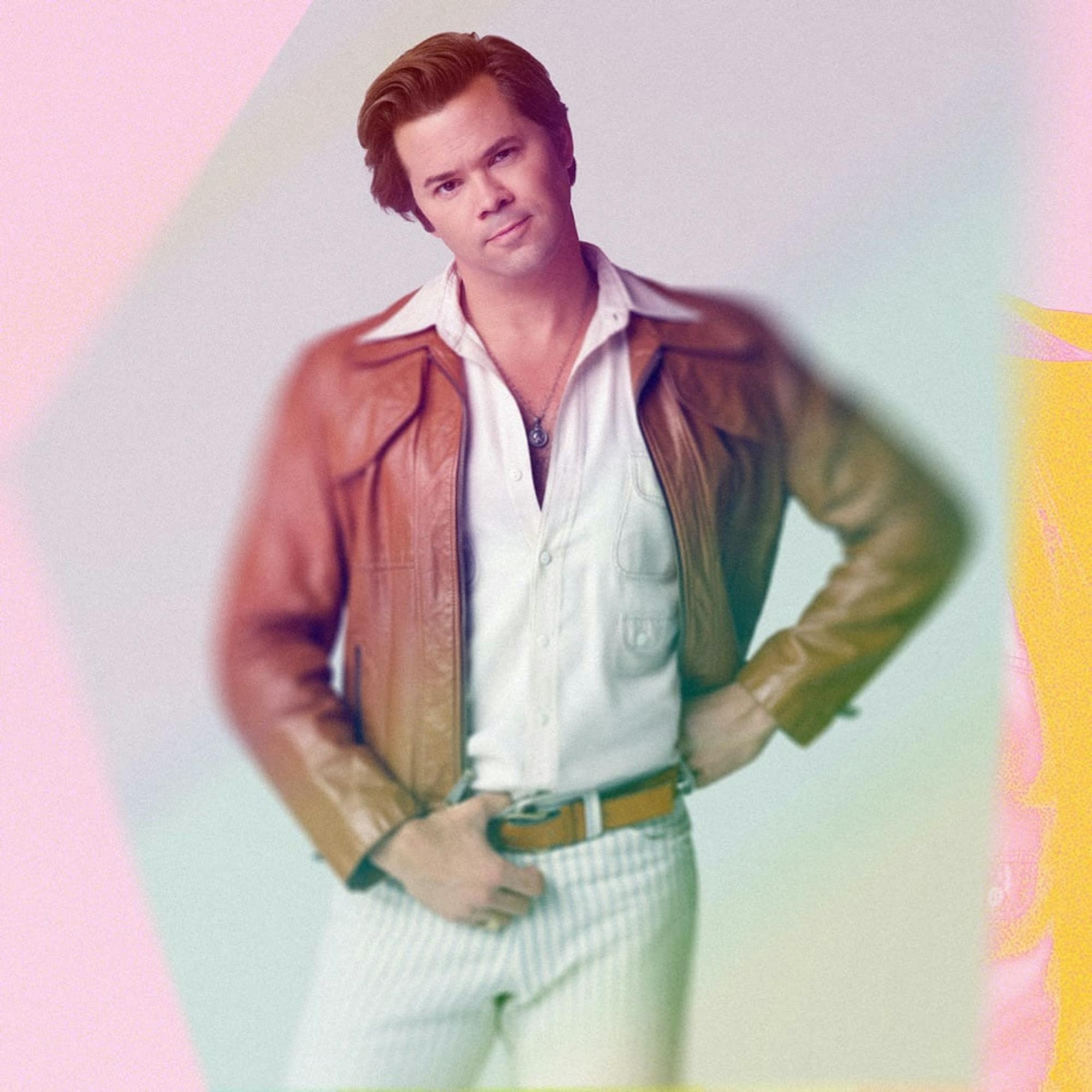

Jim Parsons

Matthew López: Joe, you directed the Broadway revival with the same cast in 2018. Can you talk about the process of translating the story from stage to screen?

Joe Mantello (Director): It was extraordinary that we got to rethink something that we all had previous experience doing, but we got to do it in a new form. Early on, I asked Ryan Murphy, our producer, for a week of rehearsal on that set. It made an enormous difference because we got to shake the cobwebs out of what we knew, and we also got to start to rediscover a new version of what this might be. Having the benefit of a Broadway run was enormously impactful, certainly in terms of the amount of material that we were able to do each day — some days, we were doing eight or nine pages, which is kind of unheard of... Each one of the performances on the screen became richer, and more organic and effortless.

What was the process like of coming back to these roles and recapturing the performances in a very different way?

Jim Parsons (Michael): The only really challenging part of transferring this to film was my fear of it not living up to what had been such an incredibly positive, impactful, and profound career and life experience. Once we were doing it, feeling the camera there and understanding the new audience that we were playing to, it felt great. I’ve never done anything on camera that had that much research, rehearsal — just this bedrock underneath it that allowed you to play at a level that I’d never been allowed to play on camera before.

Each one of the performances on the screen became richer, and more organic and effortless.

Joe Mantello

Matt Bomer (Donald): The word that comes to mind is freedom, really. We had this implicit trust built in with a cast we loved, and we knew we had one of the best directors in the world to modulate us. It did allow for a respect for everything that we had learned from the theatrical production, but also the openness to whatever was there on this incredible set, in this incredible new world we were living in. From take to take and from scene to scene, just experiencing that freedom was one of my favorite parts of this.

Robin de Jesús (Emory): It was so great to enter a room where you felt so comfortable because you knew the material so well. It was easy to bounce off of one another, because you’ve learned each other’s vibes and energies. But it was also interesting to clock, oh, wait, I don’t want to get too comfortable either. I don’t want to miss out on the new discoveries that might be different because I’m so stuck in my ways. You know this material so well, but also don’t let that get in the way of being present.

Robin de Jesús

Matt Bomer

What did you learn that you didn’t expect to learn about these characters and your performances on set?

Brian Hutchison (Alan): That you can be quiet, at times, and it can get across. You can almost whisper. You can do things with a glance. When I saw the film, I thought it was amazing how everybody could do something with just a moment, a look to someone else, a look away. We have to project that to hundreds of people every night when we do the play, and you have to use a certain volume, and you have to sometimes get information across to the very back of the house. There was something really freeing in being able to take it down.

When the play premiered, it was scandalous, and it was also hugely successful. When you revived it 50 years later, it was not scandalous, but it was also hugely successful. What is it about this story that is for a contemporary audience?

Zachary Quinto (Harold): For me, there’s a universality to this longing for both connection and acceptance of self. Each one of these characters represents a different perspective on what it means to belong in the world — certainly in this filter, what it means to belong as a gay man, but it goes beyond that; it touches on some ephemeral human need to be both represented and loved. A lot of the characters make the mistake of thinking that that love can be found outside of themselves, but the reality is that it has to be discovered and generated from within. That’s something that contemporary audiences, whether they’re gay or straight, will be able to recognize in themselves, I hope.

Mart wrote his truth.

Matt Bomer, on playwright Mart Crowley

When they were casting the original production, they had a hard time finding actors willing to play openly gay characters. Now, this cast is full of openly gay actors. What role do you think this piece of theater played in changing the landscape for actors?

Tuc Watkins (Hank): This is a period piece. It’s specifically set in 1968. Sometimes people say, “Why didn’t you update it?” I think Ryan Murphy answered that best when he said, “We need more stories about L.G.B.T.Q.+ history.” We need to know our history better. We need to know what it was like to be a gay man in the late 60s. It was, in a nutshell, not easy, and any freedom we feel now is because we’re standing on the shoulders of the giants that came before us. It’s important to look at that.

Bomer: Personally, what I feel was so radical and courageous in what Mart was doing is if you look at some of his contemporaries, like [Edward] Albee and Tennessee Williams, they were writing about L.G.B.T.Q.+ themes but masking them behind other characters. Mart wrote his truth. He put these characters out from what he knew and what he experienced, and there was something radical and revolutionary about that at the time.

Zachary Quinto

Brian Hutchison

This March, Mart Crowley passed. What has his life and his work meant to you personally?

De Jesús: The thing that always gets me — that is shocking every time I think about it — is that despite him writing this show in 1968, it is still way more diverse within its gay community than most playwriting today. You look at our characters and we’re all so different. Some[time] after that, it was like gay — that one adjective meant all these things, and so when you played gay, you played this certain archetype, right? You look at this, and this is more interesting than a lot of the stuff getting written today.

Michael Benjamin Washington (Bernard): I had the great honor of getting to know Mart in a very personal way. We would talk about playwriting, which is a passion of mine. The great resilience that he had — the foresight he had, and writing what he knew — is one of the greatest examples of, If you’re going to tell stories from your tribe, do it responsibly, because it will outlive you. He was so excited by this production and what Joe was doing. When a playwright can write something as magical as he did and then release it to the world and release it to a new generation of creatives and say, “Do your version of it” — that’s what I’m going to try to take from his life and legacy.

There’s so much about this experience that was magical and celebratory.

Zachary Quinto

Quinto: There’s so much about this experience that was magical and celebratory: Getting to work together, getting to see the impact that it had when we did it in New York. But the most incredible part of this whole journey was watching Mart enjoy that success, and standing with him on the stage at Radio City when he accepted the Tony for Best Revival, and seeing the joy and the presence with which he received that moment. It is sad for us to know that he won’t be able to experience the premiere of the movie, but joyful to know that he experienced the filming of it and got to really participate in everything and fully inhabit it and fully enjoy it. I’ll never forget those smiles of such well-deserved recognition that he got to appreciate.

Charlie Carver

Michael Benjamin Washington

Michael and Robin, can you speak about the experience of working on these characters who are navigating the white world as two gay men of color in 1968?

De Jesús: I’m an Afro-Latino with a very close proximity to white folks. I navigate in a world where I’m very fluid and pass. And in a world where we’re finally talking about anti-blackness, and so many of us are trying to confront that, I thought it was really beautiful to be able to showcase the nuances of anti-blackness and racism within people of color as well. I’m just proud to have that conversation, and I’m proud for my people to see that conversation on display.

We’re no longer trying to knock on a door to get someone to see us. We see us, and we decide it.

Michael Benjamin Washington

Washington: It was an incredible honor working with Robin. I often thought that if he missed a performance, I would probably have to miss one too, in New York, because I wasn’t interested in the play as written. I was very interested in the Joe Mantello production in 2018 with these men, particularly Robin de Jesús, because the conversation does shift. It doesn’t become a play about a Black guy taking racist quips from the white guys. It’s a completely different navigation of emotion. So, that marriage worked very well. But it’s all Joe Mantello. He kept me tethered to Robin and kept me tethered to the story.

De Jesús: Just add to that the beauty of seeing our gay stories in that time period that so often erased us. It really is a game changer to put us in a period piece, because so often people think that we didn’t exist in that time. They think we just appeared in the 80s.

Andrew Rannells

Tuc Watkins

What is the legacy of The Boys in the Band? And what do you hope people will say about your contribution to it?

Watkins: More than anything, I hope that people are entertained. But it really is a peephole into what it was like to be gay 50 years ago, and how we now live differently because they had to live the way that they did but some of them stood up and were counted.

Hutchison: Everybody in the film is longing to connect. Through a lot of angst and deep, deep longing that can’t even be admitted, there is this sense of wanting to connect and wanting to find someone, find love. There’s something really beautiful in that because that wasn’t possible at that time and it is now.

Any freedom we feel now is because we’re standing on the shoulders of the giants that came before us.

Tuc Watkins

Charlie Carver (Cowboy): There’s this essence that exists in the play, somewhere between the words, that is a string through time until right now, and will forever be. There’s a queer spirit in there. It’s about our history. It’s about who we are and what we bring to the world.

De Jesús: I feel like the movie should have a second title. It should be: The Boys in the Band: We Can’t Go Back.

Washington: I’m most excited to see what the legacy is going to be from a new generation. I’m excited to hear how they receive it, remembering that 50 years ago this was the only image, and now we’ve had 52 years of examples and stories being told. The great thing about right now that I hope people really honor is that we also have gay men in leadership and power positions who made this happen. We’re no longer trying to knock on a door to get someone to see us. We see us, and we decide it. The Ryan Murphys and the Joe Mantellos and the David Stones — all of these people decided to tellourstory now. That’s important to remember, too.

Mantello: If anything, what you walk away from this film saying, I hope, is, Those were nine extraordinary performances, and that’s one hell of an ensemble.