Laverne Cox and Angelica Ross on Disclosure and the past, present, and future of trans representation.

When Laverne Cox met Angelica Ross in 2013 at The Trans 100 celebration in Chicago, neither of them had yet begun to enjoy the kind of mainstream success that they can claim today. “I remember when I first met Laverne, she had on her flats. Miss had on a little sweater. Very humble pie,” Ross says. “She talked about a new show she was going to be doing on the internet or Netflix or something.” Adds Cox: “I didn’t know what was going to happen.”

What happened, of course, was that Orange Is the New Black put Cox on the map, propelling the actress to four Emmy nominations and cementing the trailblazer as an icon. Ross, meanwhile, has since starred in such critically acclaimed series as American Horror Story and Pose, and she’s triumphed as an entrepreneur with her organization TransTech, a talent incubator designed to economically empower transgender people.

Angelica Ross in Pose

Photo Courtesy of Netflix

Laverne Cox in Orange Is the New Black

Photo by Paul Schiraldi / Netflix

Both of them lend their voices to director Sam Feder’s documentary Disclosure, which Cox also executive-produces. The film offers a comprehensive look at the ways trans people have been depicted onscreen over the decades, and at the impact of those representations on generations of audiences.

“I always wanted to do something that in my mind I called ‘the transgender Celluloid Closet’” Cox says, referring to the groundbreaking 1995 documentary that in some ways foreshadows Disclosure.“ That film looked at the history of gay and lesbian representation in Hollywood. For years, I was like, ‘We need something like that for trans people.’ I apparently spoke it into existence. I met Sam, and three years later here we are.”

Tre’vell Anderson: Laverne, you have a great, long knowledge of trans history and representation. What moments were important for you to include in the film?

Laverne Cox: There are so many things. My first memories of seeing what I thought was a trans character onscreen come from Edie Stokes on The Jeffersons. Then there’s also the relationship between drag and trans. My mother was a huge fan of The Flip Wilson Show and that Geraldine character. Even though that was not a trans character, I believe the history of comedians — particularly African American comedians — dressing in drag affected the ways in which people responded to me in my gender nonconformity when I was a kid, and later when I transitioned. I knew we needed to unpack the impact of those representations on the lives of trans people, and on my life as a trans person specifically.

Edie Stokes, played by Veronica Redd, on The Jeffersons

The Jeffersons © CBS 1977

Geraldine Jones, played by Flip Wilson, from The Flip Wilson Show

The Flip Wilson Show © NBC 1970

Angelica, you smiled when she mentioned Edie Stokes on The Jeffersons. What’s your connection to trans imagery prior to this particular moment?

Angelica Ross: I really did gravitate toward these same characters, these strong women who weren’t necessarily trans, but they were not the ingénue.

I appeared on The Maury Povich Show twice. I remember growing up in my family household, Jerry Springer would come on and my mom would be like, “None of my kids better turn out like that!” Then, years later, my housemother encouraged me to take the call to go to Maury Povich. For us in the trans community, it was like the casting call of all casting calls. We were taught that allowing the media to exploit our lives was one of the ways we could be discovered. I’m so grateful we have other avenues now.

LC: So many legends from our community were on those shows. As exploitative as they were, there’s something beautiful about looking back and seeing the showgirls from the 90s who were just epic and legendary — even as they didn’t necessarily teach the best lessons to cisgender people about who trans people were.

AR: The fact that we were there made a huge difference in a way that I did not expect. What ended up happening was that behind the scenes I had a conversation with the producers. I told them about how problematic this was, the way we were doing the show. All the girls came together and rallied behind me as I spoke. From that point on they started saying, “She was born a boy.” That little change in language happened because we spoke up.

I have to say that as negative as that portrayal could be, there was always a silver lining in it. The silver lining from the beginning was that trans people at home were seeing these bitches standing there like, I don’t give a damn. I’m standing up next to these hoes and I’m storming the building! That was one side of it. The other side, for me, was that all of a sudden I was being called a man by an entire audience. My worst fear became true.

LC: Was it traumatic?

AR: Girl, it freed me. I’m sitting here looking stunning and that’s the best you got? You can call me whatever you want to call me, but you’re going to call me successful.

They didn’t know what to do with us back then, so we’re taking the Jerry Springer job, we’re taking the Maury Povich thing. Now we have stories like Pose and other shows that aren’t L.G.B.T.Q.+ centered that are finally including opportunities for us to show what we can do.

LC: What is so beautiful about what you just said, Angelica, and about this history, is that we’ve always found a way. Whether there were opportunities or not, we created them, we made them happen, we made them work for us. To actually have that documented is really important so that we understand that we’ve always been here. We’ve always been finding a way out of no way.

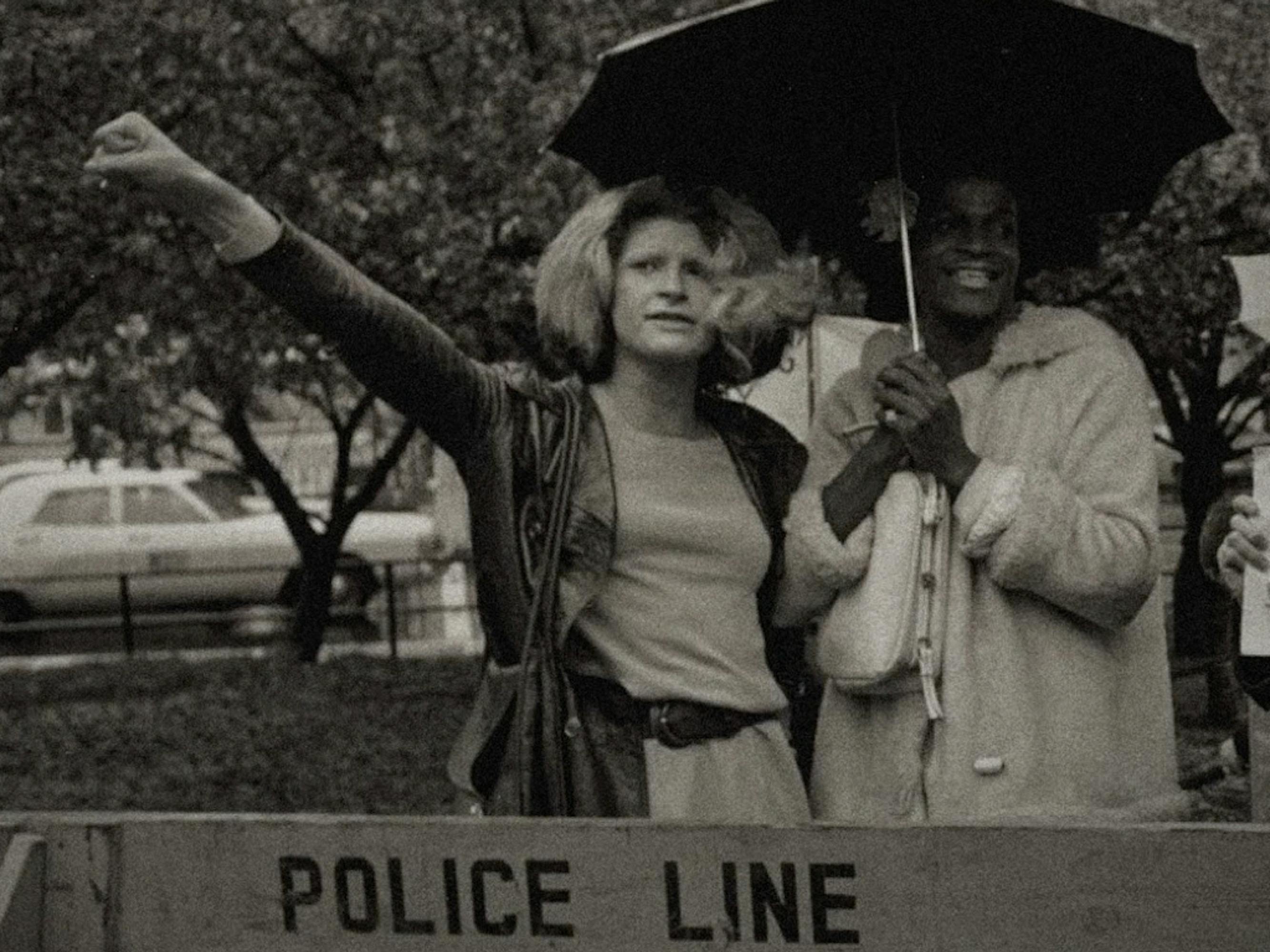

Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson stand at the front lines of a protest in New York City, 1973

Photo Courtesy of Netflix

An activist holds up a Black Trans Lives Matter sign at a Trans+ Pride rally at Parliament Square in London on September 12, 2020

Photo by Alex Mcbride / Getty Images

One of the things that Disclosure does so beautifully is it takes all these very different images and moments and allows us as a community to grapple with the positives and the negatives. You both are folks who we look up to, folks who have broken through to the mainstream. I wonder what those accolades of being “the first” mean to you.

LC: It’s complicated. I’m proud that I’m still alive, to be honest, and I’m proud that I didn’t give up when I wanted to give up on my dreams of being an actor. I’m proud of what I’ve accomplished. But there’s a lot of pressure that has come along with that.

When I was on the cover of Time Magazine, I was very cognizant that I was only there because of so many people who had come before me. I was like, “There’s so many more of us, and there are so many more stories.” My experience is not Angelica’s experience. It’s not Tre’vell’s experience. That’s what I wanted to highlight. As I was saying this, I felt like it wasn’t fully being received; people just wanted to hear about Laverne. That was hard.

It’s been so beautiful, though, over the years, seeing Transparent happen and seeing Pose happen — and Euphoria, Billions, A Fantastic Woman. Other people are having opportunities to shine. For so many years people were saying that there were no trans actors. You can’t say that anymore.

Angelica, how has it been, growing into the visibility that you now have?

AR: It’s not easy, but it’s not the worst. People don’t know what the trajectory of celebrity looks like. They think that you’re actually rich when you are famous. The reality is that I was very famous before I was coined up, which became very problematic for me as a Black trans woman.

We’ve got a world that takes advantage of the most marginalized and puts them into the sort of workhouse of nonprofits. We’re the faces of how they attract money in many ways, but half the time the money doesn’t trickle down to our communities. You have to be someone who is willing to withstand the years that it takes for folks to know that I’m serious, I’m still here, I’m not going anywhere. Yep, I’m on TV, I’m doing movies, I’m doing fashion campaigns. But guess what? I’m still holding things like the TransTech Summit for free, and we’re paying our trans and nonbinary facilitators a stipend to share their skills.

Laverne, could you tell us how you put together the Disclosure team?

LC: We were committed to making sure that everyone who worked behind the scenes was also trans. When we could not find someone trans to fill a role, Sam Feder had the idea of creating a fellowship program where a cisgender person would train a trans person. That created an environment that was so uplifting. Everyone was invested in the material and in the subject matter.

So much of the conversation around diversity and inclusion in the entertainment industry right now is that it is crucial that we have diverse folks in writers’ rooms and crews behind the scenes. But how do we cultivate that talent? What are we going to do to provide opportunities for that talent to cultivate themselves so that they’re prepared when the call comes? That’s a little thing that we tried to do on this film.

Has the way that people are responding to Disclosure — as well as to the increased opportunities that members of our community have — changed how you approach the work that you’re doing?

AR: For me, Disclosure was just further proof that trans people being in charge of trans narratives is a good idea. It really is an opportunity to teach people how to love and treat and support us as a community. I want to give folks a heads-up about what this industry is really about. It ain’t an overnight success. It took me about 10 years to become that overnight success. I want to be involved in creating the space for my community to shine.

LC: What I feel is possible post-Disclosure is for us to really have more sophisticated narratives around trans people. Collaborating with some cis folks who’ve written trans narratives with the very best of intentions, I’ve found that they have no idea why they’re problematic. Post-Disclosure we have to elevate the conversation. We have to make different decisions about how we tell stories. We have to be accountable now, right? I can’t wait for these projects to get going so we can really move to the next phase of what trans representation can be.

The film came out during this particular year of all years. What does that say about where we are as a culture in terms of representation onscreen and in terms of how we’re treating each other in everyday life?

AR: We are at a point right now where we’re so used to the same white people telling the same stories from the same direction. What we’re seeing with Disclosure is that we can actually get through to people. If the lion is finally telling the stories instead of the hunter, then maybe we’re not shooting and hunting lions. I think our humanity is being heard because our voices are being heard, and our voices are being heard because now is the time when folks are starting to amplify what we’ve been saying all along.

LC: I also believe that Disclosure gives us an opportunity to think about media in general and how it can indoctrinate us, how it can teach us how to think about ourselves and about each other. What I love about Disclosure is that it’s really about developing a critical lens around the ways in which we see. There are things coming at us that are just full-on propaganda, and we, as citizens, as human beings, have to be able to have a critical relationship to everything that we’re receiving in the media. Disclosure gives us a wonderful template with which to do that.