In the documentary Dick Johnson Is Dead, filmmaker Kirsten Johnson asks her father to meet his destiny before it arrives.

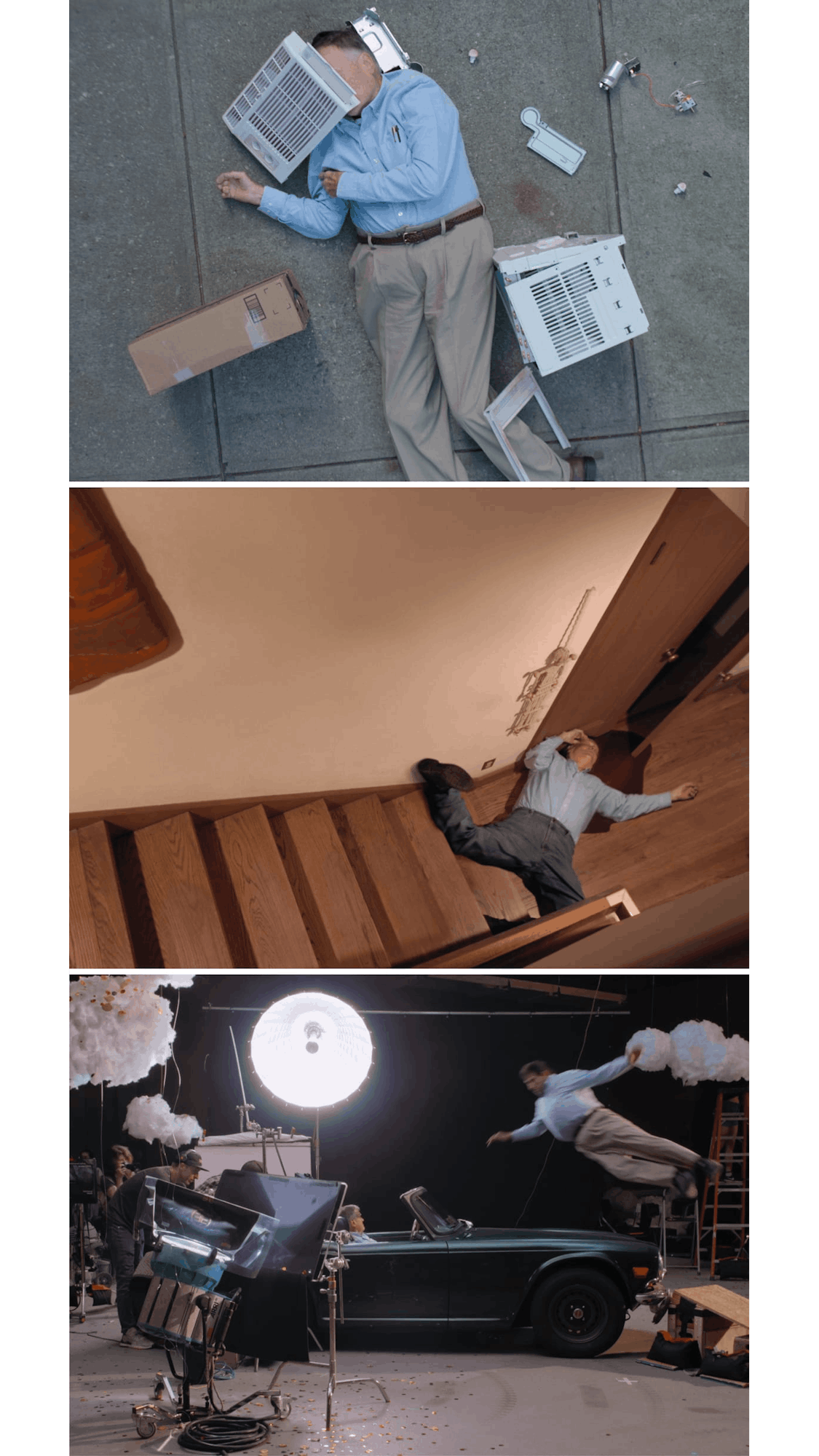

It all begins when an air conditioner falls on Dick Johnson’s head. Later, the 86-year-old retired psychiatrist falls down a staircase to his death. He’s killed in a car crash, he’s struck by a two-by-four, he ascends to a strange and colorful heaven.

In sequence after sequence of the documentary Dick Johnson Is Dead, award-winning filmmaker and veteran cinematographer Kirsten Johnson (Cameraperson) works with her beloved father to stage his ultimate demise. In between these quasi-fantasies, she captures his cognitive decline: The project is a prelude to the real thing, an exercise in confronting dementia — a disease that also afflicted the filmmaker’s late mother — and a preemptive response to the inevitable.

In a conversation with acclaimed documentarian Yance Ford (Strong Island), Kirsten Johnson discusses the fear and joy of making Dick Johnson Is Dead. “I have known all my life that I pulled a lucky card with my dad,” she reflects. “I didn’t know he was a movie star.”

Yance Ford: You say at the beginning of the film that you began to realize that you were losing your father. It feels like that realization was the catalyst for making Dick Johnson Is Dead.

Kirsten Johnson: We conceived of the film as an experiment together. Really early on, I realized: I’ve started this all too late. He already can’t do things. Then out of nowhere — he wouldn’t know where he was in time, space — all of a sudden, he’d be like, “Boom, here’s where we are in this scene.”

Never accepting his absence, always fighting for the ways in which his presence could manifest — I think a lot about that. The body is present. The body has a story. The body can transform in relation to your own story.

It was incredible to hear him talk about the impact of his memory loss on the people around him. That self-awareness, despite the dementia, is remarkable.

KJ: I will give you a classic [example] of self-awareness: He wakes me up in the middle of the night, and he’s dressed and headed for the door. I’m like, “Where are you going?” and he’s like, “There’s a patient waiting downstairs.” We’re in New York, he’s retired, he’s not got any patients. I’m like, “Dad, there’s nobody downstairs. It’s three in the morning. What kind of patient would make an appointment for three in the morning?” He said, “Somebody desperate, someone who really needs to talk to me.”

So we go downstairs. He looks around and he says, “There’s nobody here, is there?” I said, “No.” He said, “Wow, it must really be hard to watch your father losing his mind.” He’s like, “O.K., call the guys with the little white straitjacket, I’m ready to go.” Then he turns and he’s like, “But you’re really gonna miss me!”

The film pushes the audience by deploying humor as the prism through which we examine our fears around death.

KJ: My father loves humor and has a light-on-his-toes kind of way. I can be incredibly earnest, so it can be challenging to be funny in other people’s territory. I could do this with this film because this ismyfather: I can mess with my father; he can mess with me. The freedom in that relationship was really liberating.

I will say also that making Cameraperson was incredibly liberating to me, and there was only one laugh in that film. I was like, Really? We made an hour-and-a-half-long film, and there was one laugh? So I was really committed to there being humor in this film.

Let’s talk about Cameraperson: You erected this film that shed light on how you have worked over the course of your career. What are the connections that you see between the two projects?

KJ: When we finished Cameraperson, I really did not know if anyone else would understand it or relate to it, but I knew that I had addressed my own need to the utmost of my capacity. I had broken something for myself; I had broken something formally. So I said to myself, I must make what I need to make. I will only make something that is pushing boundaries for the form, for myself, for the collaborators I’m working with.

The gift of how appreciated Cameraperson is in the world gave me freedom. I really felt with [Dick Johnson Is Dead], I can fail, I’ve actually set myself up to fail. I’m going to try to make my father immortal, that’s my plan. It is implicitly a movie that will fail, and I’m good with that. I’m going to give it my honest love of the craft, I’m going to give it everything I know I care about. But I’m not going to give it the things I know, I’m going to give it the things I wonder.

Death makes many people uncomfortable. How did you succeed in pitching this film?

KJ: I said, “I want to make a film about killing my father over and over again until he really dies for real.” People would laugh, and that was it. I would be at a pitch session, and I would be asking the people who I was pitching to: Had they thought about how they wanted to die? Was there a way they were afraid of dying? We were having these unbelievably deep, amazing conversations. That’s what this movie is: It’s an experiment around how do we talk about it, can we talk about it, can we laugh at it.

One of the things that Dick Johnson does so well is bridge the fear of losing your loved one with the eventual reality of it, by creating lots of different visual tableaus for that loss. That makes it easy to plug into.

KJ: Who has inspired me are people who have managed to craft things of their pain, craft action out of outrage — transform, build, and in some cases tear down, too. What I knew from making Cameraperson and from shooting films with so many other incredible directors is that things that you don’t expect get made from the strangest juxtapositions. The moments when you think all is lost, something appears that restores your will to live. That’s the gift of making things and sharing the love of movies with people: We connect over the pain. We forge new things. We build new societies and new rituals.

How is your dad? How is Dick Johnson?

KJ: Dick Johnson, Dick Johnson. You know, my father had been living with me for three and a half years. In July, we realized there was no way for my brother or for me to be able to provide 24/7 care for my father, so he is in a dementia-care facility near my brother’s in Bethesda — a small home of about eight people. It has ripped my heart out of my body, and it has also been what was necessary.

I feel all that, and then I call him up: “I’m doing an interview about Dick Johnson Is Dead.” We dial him in, and he talks about the movie, and he is himself.

What’s next for the movie?

KJ: Releasing it into the world! It is a film that connects to people who have dementia, people who have parents who they cannot see in this moment, the healthcare workers who take care of the people we love when we can’t ourselves. It’s going out into those worlds where people have to cope with pain all the time. And this movie’s funny. In the intensity of this moment, the people at the dementia-care facility where my father is, they’ve watched the movie five times, and they love it.

I hope that this film helps people be less afraid and less in denial. If you choose love, collaboration, laughter, together you can face the most terrifying things. That’s what we all have to do as humans. We all have to face death, even if we think we can get away with avoiding it forever.