Director George C. Wolfe reflects on Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom and the Mother of the Blues.

George C. Wolfe was staging his 2018 production of The Iceman Cometh when his star, Denzel Washington, pitched the idea of adapting Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom for the screen. “I’d never done an August Wilson play,” Wolfe says, about directing a work by the Pulitzer Prize-winning legend of Black American theater. “I like the danger of what might not work. I breathe in a very interesting way inside of that kind of energy.”

Wolfe has few rivals in the theater world. The Kentucky native came to prominence in the early 1990s with the musical Jelly’s Last Jam, which earned an impressive 11 Tony nominations. Shortly after, he took home the prize for directing Tony Kushner’s Angels in America: Millennium Approaches. Then he won again for the musical Bring in ’Da Noise, Bring in ’Da Funk. Moving into the cinema with similar success, he directed dramas Lackawanna Blues, Nights in Rodanthe, and The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks.

There’s a feeling of urgency to his new film, scripted by Ruben Santiago-Hudson and produced by Washington. Viola Davis brings awesome swagger to real-life blues icon Ma Rainey, and Chadwick Boseman is electric in his final performance, as Levee, a strong-willed trumpet player hungry for stardom. It’s 1927 and Rainey reluctantly heads north to Chicago for what turns into a combative recording session. As her band (Glynn Turman, Colman Domingo, and Michael Potts) waits for her in the studio, Levee announces that they’ll be recording his own arrangement of Rainey’s signature song. At any cost, he’s eager to shine — maybe brighter than the Mother of the Blues herself.

Yet once Rainey turns up, it’s clear who dictates the rules — and it’s not the white manager, nor his bosses, and certainly not Levee. “One of my early friends in New York had this saying: ‘You got the right idea, but the wrong bitch,’” Wolfe recalls. “It’s a brilliant little phrase, and I think Ma was very much, No, no, no. That won’t work here. That’s how she maintained a sense of power and potency and agency in her existence.”

Creating a soundtrack to honor Rainey was a delicate task, and Wolfe entrusted it to three-time Grammy Award-winning jazz musician and former Tonight Showband leader Branford Marsalis. The acclaimed saxophonist lent his talents to Spike Lee’s Do The Right Thing and Malcolm X, and scored the 2010 Broadway revival of August Wilson’s Fences. Part of a prolific family of musicians that includes his brother Wynton and father, Ellis, he has recorded with the likes of Art Blakey, Terence Blanchard, and Dizzy Gillespie, and with James Taylor, Sting, and the Grateful Dead.

For Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, he assembled a topflight group of New Orleans-based musicians to perform Rainey’s classics. “Thank God I was from New Orleans,” he says. “Those guys still play in that style. There’s a certain kind of authenticity.”

To celebrate the film, the music, and the Mother of the Blues, Queue brought Marsalis and Wolfe together in conversation about Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom.

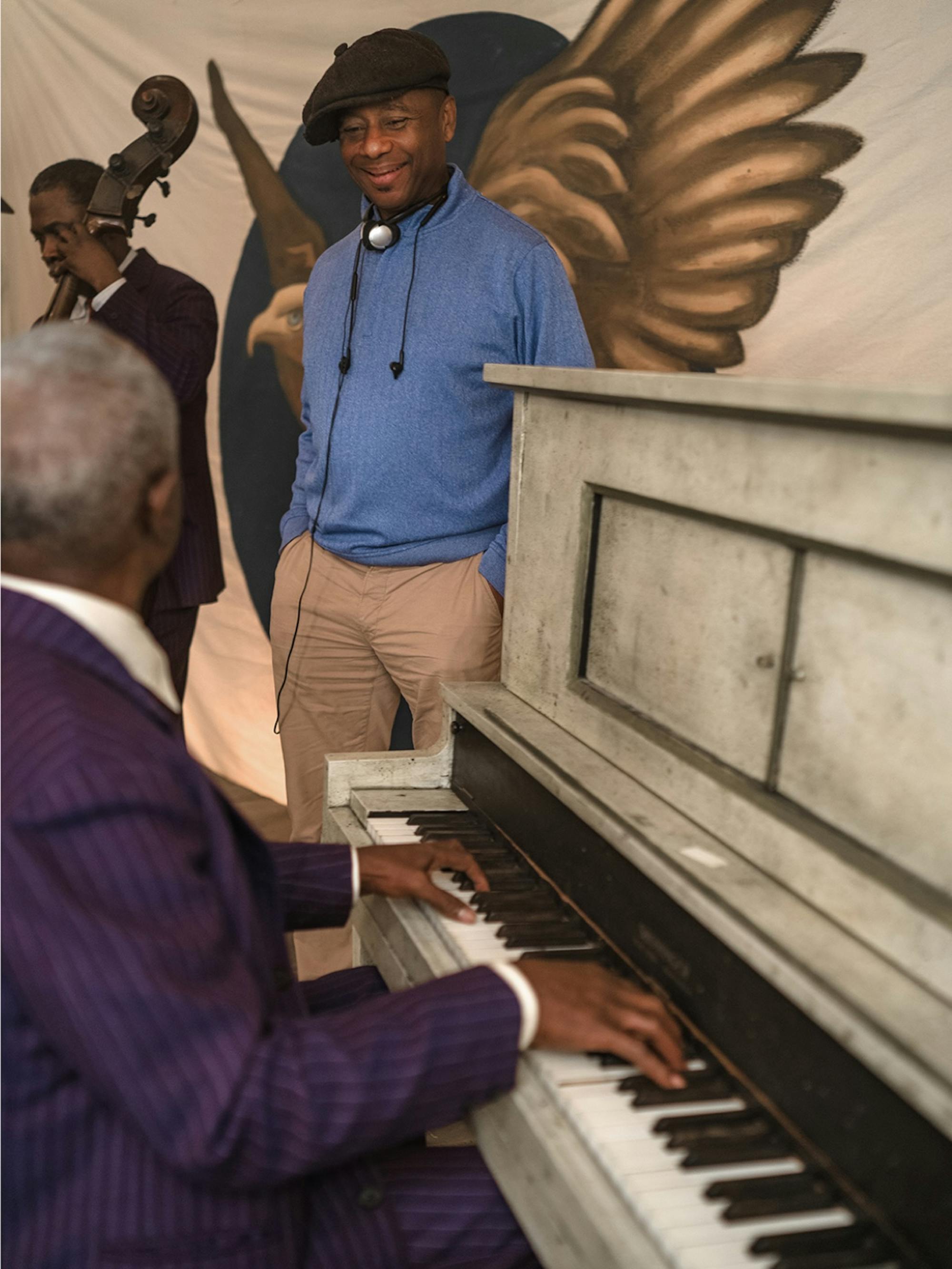

George C. Wolfe directs Viola Davis and Chadwick Boseman in between takes of Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom

Branford Marsalis: When you started researching Ma Rainey, what did you discover about her?

George C. Wolfe: I was fascinated that she didn’t do the East Coast journey, that she didn’t wind up in New York, that she didn’t get celebrated there. Initially, I was intrigued that she didn’t go the Bessie Smith route. Carl Van Vechten, who considered himself an expert on Black American culture, wrote an article in Vanity Fair in 1926, stating the greatest blues singers were Bessie Smith, Clara Smith, and Ethel Waters. Ma was not included.

She had the gold teeth and jewelry and fans who were devoted to her. She sang the blues like nobody else and was an out, unapologetic lesbian. She was also an entrepreneur and in charge of her art. And there are only — as I was to discover — six or seven pictures of her in total on the planet. She didn’t turn into a visual icon at all. She was an icon based on her voice and what she sounded like, but was never a pinup girl — and I’m being facetious, but she never really was.

That sense of legacy, there’s something so extraordinarily empowering about that.

George C. Wolfe

BM: There’s a reality to that. Wynton and I grew up in New Orleans. My dad stayed in New Orleans and never became a pinup. Wynton moved to New York and ta-da! Bessie Smith moved to New York; Ethel Waters was in New York. There’s a line in the movie where Ma says, “I don’t like it here no way. I can just take my Black ass back to Georgia.” There’s a reality to that, to her connection to the South.

GCW: “I can carry my Black bottom on back down South to my tour, ’cause I don’t like it up here no ways.” That line was a huge clue for me as to what I think August was writing about: When Black people moved North, something was lost. There’s a power and a sense of belonging that is connected with having land, with owning land. Yes, you’re ducking and dodging people trying to destroy you, but the land is yours. Yes, people are trying to steal it from you, but it’s yours. You have this sense of belonging, and that is connected to who it belonged to before. In New Orleans, people are living in the houses that their grandfathers and their grandmothers lived in. That sense of legacy, there’s something so extraordinarily empowering about that.

Being in the South, with the Jim Crow laws and the Confederate statues and the lynching and the violence, all of that suggests having no power. But Ma Rainey was able to build an economic base and be in charge of her music and her art, and take care of other people. I really wanted to convey that dynamic in the film so that when she goes to Chicago and she has attitude, it’s not attitude based on personality or posturing, but attitude based on legacy, history, and accomplishment.

Branford Marsalis behind the scenes with Ma Rainey’s band

BM: Didn’t she own two theaters?

GCW: She owned two theaters in Georgia. I had my assistant track down her touring schedule for a year. It included 40 stops, sometimes in theaters, sometimes in tents. She was this showbiz entrepreneur, a Black woman who was in charge of herself and her career and her voice.

BM: She wasn’t going to own any theaters in Chicago, that’s for damn sure.

GCW: That was not going to happen. As much as the Apollo was home for so many Black artists, a Black person didn’t own the Apollo. All the lines that Ma is given by August are talking about, Ma listens to her heart, Ma listens to her voice. She understood the intimacy that is involved in the making of art, and she was a ferocious guardian of that fragility and of that truth. She had to be, because she understood and what was at stake.

BM: What are the differences, lyrically, between working on a movie and working on a play?

GCW: I have this theory that theater, for all of its language and storytelling and characters, is ultimately about ideas. You watch a play like Angels in America, or like Ma Rainey, and you’re caught up in the drama of the moment, but what you take away are the ideas that are bubbling underneath. Film is about what’s happening next.

The play is called Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, but it’s an hour before she appears. I wanted to introduce the audience to the combustible dynamic between Ma and Levee as soon as possible. I did that in what I call the prologue. First, when we see Ma singing, it’s her and her congregation, i.e. the Black folks of the South celebrating her, basking in her, claiming and owning and finding their story in her song. When we get to Chicago, the audience becomes disembodied, and we end up watching the interplay of the characters. Ma is performing with her dancing girls, and Levee feels a solo coming on. Because he feels it, the whole world needs to see him feel it, so he makes a decision to strut downstage so that the world can watch him reach for this musical moment, which is a direct violation — it’s “Ma Rainey and her band,” not “Ma Rainey and Levee”; which in turn becomes the first shots fired in a war between these two powerful characters.

Ma was speaking for people who needed to be heard.

George C. Wolfe

BM: When you asked me to write the music, I immediately started compiling a list in my head of which musicians would work. As you started to read the script, did you visualize the principal actors? Did you always see Viola as Ma, and Chadwick as Levee?

GCW: Viola was involved two seconds after I agreed to direct. Denzel and I, we both said, “Viola. End of conversation.” Then we asked Chadwick and he came on board to play Levee, thank God. We just went on from there, adding in Glynn Turman and Colman Domingo and Michael Potts. When you have certain pillars, with a Levee and a Ma Rainey, the more you cast it, the more it becomes clear who fits into the landscape you’ve created.

Let’s go back to the musicians. There were some that you went like, “Yes” and “No.” What was that criteria?

George C. Wolfe and Dussie Mae actor Taylour Paige have some fun behind the scenes

BM: The first question is trying to get musicians that play in that style and play with that kind of authenticity. It was important to find guys and gals who have really strong personalities. Wendell Brunious, the trumpet player, the cornet player, was perfect for Levee. He’s a New Orleans guy, he’s like, “Hey, y’all. How you doing? Come here, girl. Give me some sugar. Give me a hug.” That was the whole thing; these guys have really strong personalities, and those personalities match the personalities of the actors.

GCW: One of the things I always say about [Bring in ’Da Noise, Bring in ’Da Funk star] Savion Glover is that he is this living repository of rhythms. Old tap dancers passed those rhythms on to him, and those rhythms were passed on to them by old Black tap dancers. There’s a sense of continuum, and if you go back far enough, you’re connecting it to Ma’s sound; you’re connected to something that is ancient and potent and knowable and unknowable at the exact same time, so that when you’re in the presence of it, you surrender.

An audience can tell when they are in the presence of a recycled truth. And they can tell when they are in the presence of an authentic truth that was crafted just for them. It exists in acting. It exists in sound. It exists in the textures of the visuals. You can tell when you are witnessing something that is layered with history, and you can tell when you’re in the presence of something that is not. You can smell it.

BM: Even though an audience member wouldn’t articulate it as such, it’s exactly what you’re saying.

GCW: They respond viscerally and emotionally to the sound. It’s one of the things that I love about musicals and plays that use music: Somebody has to talk for 10 minutes in a play before an audience decides whether or not they’re going to trust that voice. You hear don-don-don! and you instantly surrender to the musical phrase because there’s truth in that sound. You don’t fight it. Your body knows it should surrender and trust it.

Left to right: Michael Potts, Colman Domingo, Glynn Turman, and George C. Wolfe

BM: When I was watching the scenes and writing the music, the thing that really knocked me out is that it didn’t feel like an imitation of 1927, it felt like 1927. What they were dealing with is the same thing that people deal with right now. When you can make that connection, when the story suddenly becomes your story — and it’s not bogged down by the costumes or the technology or the period — it’s really amazing.

GCW: I hate nostalgia. I wanted everything to feel as though it was crackling and in the moment, it was breathing completely and totally in 1927. If it’s through a lens, then you get to sit back and relax, and you can feel superior to it or distant from it. I believe on a project if I can locate the intimacy underneath the language and the urgency underneath the language, then I know I’ll be able to do it.

I always tell actors, “If you want me to stick around for the pain, you’ve got to invite me to the party.” We need to see the joy and the light and the possibility of Levee — his charm, his personality, how he’s in command of everything — and to fall in love with him, to fall in love with all of these people, so that when they end up in the pain, we feel the loss as well. And that’s about actors being fully in the moment from the very start.

BM: Every time I see Levee finally express his rage, I’m stunned. It still shocks me, even though I know it’s coming.

GCW: All the disappointments that can happen to one over the course of a week or a month or a year happened to him in one day. He gets fired. His band and a recording session featuring his music that he thinks are going to happen don’t end up happening. He gets robbed. It’s a pile-up that is built on top of a hurt and a pain that happened when he was too young to really know how to process it or to figure out how to move forward from it. His success is intended to compensate for what he is lacking, but success doesn’t do that.

BM: In the end, it really doesn’t.

GCW: It just feels good and it’s nice, but it doesn’t fill in the empty spaces inside of you. It doesn’t. That’s not its job. When making art, it’s your responsibility to protect the work, but it’s not art’s responsibility to make you feel better about yourself. Art is the child that you’ve been entrusted with to honor and protect, not the reverse.

BM: Well said. Some people are going to see this movie and want to investigate Ma Rainey’s music. What do you think Ma’s legacy ultimately is in the pantheon of singers?

GCW: Ma Rainey, for a period of time, had an intensely devoted following who felt as though her voice was speaking directly to them and for them. There are people who felt that way about Billie Holiday. There are people who felt that way about Aretha Franklin. Ma was speaking for people who needed to be heard. That was crucial to her significance. I also think that the ferocity and the unapologetic energy with which she lived her life is in her sound. When you hear her voice, you can hear that sense of bravery and defiance and strength.