Director David Fincher and cinematographer Erik Messerschmidt shoot a black-and-white masterpiece for the 21st century.

It’s a milestone for any up-and-coming cinematographer, landing that first feature film assignment. For Erik Messerschmidt, that all-important project turned out to be Mank, David Fincher’s ambitious chronicle of Herman Mankiewicz and how the irascible screenwriter came to pen the first draft of what became Orson Welles’s cinematic landmark Citizen Kane.

On paper, Mank could not have been more daunting. Messerschmidt would be working side by side with a famously exacting filmmaker, on a high-profile drama starring Oscar winner Gary Oldman in the title role. He’d also be shooting entirely in black and white.

“I was like, Oh cool, I get to do black and white,” Messerschmidt recalls. “Then I realized how naïve that was, and it freaked me out. It really freaked me out.”

I’m a big believer in multidisciplinary thinking.

David Fincher

Fortunately, Messerschmidt had some history with Fincher. He had worked as a gaffer on the director’s 2014 thriller Gone Girl, and deeply appreciated his direct communication style and the specificity of his vision. Impressed by Messerschmidt’s pragmatism and work ethic, Fincher subsequently hired him for the F.B.I.-profiling drama Mindhunter, and the professional relationship deepened from there.

When Fincher turned his sights to Mank, he knew whom to call. “I’m a big believer in multidisciplinary thinking,” he explains. “Erik was obviously somebody who knew how to run his manpower, but he could also speak to his crew in myriad ways that imparted slightly different nuances. He can split hairs in terms of foot-candles or T-stops or F-stops but also have a conversation about Carol Reed or how Marlon Brando never hit his mark.”

Together, Fincher and Messerschmidt plotted how best to shoot the character-driven period drama, which was written by the director’s late father, Jack Fincher. One of the most challenging sequences was a nighttime stroll taken by Mank (Oldman) and the screen siren Marion Davies (Amanda Seyfried) through the palatial grounds of Hearst Castle. Onscreen, the friends are bathed in moonlight, yet those scenes were actually shot during the day using a classic Hollywood camera technique known as day for night. (The sequence was filmed largely on location at Pasadena’s Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens; the menagerie of animals in the background was added in digitally during post-production.)

The scope of the production might have proved overwhelming were it not for the rapport between director and cinematographer. “All we do all day is ask questions of the people that we’re working with. I was completely thrilled to be working for someone who had answers to those questions and who was genuinely interested in and curious about what it was that we were doing,” Messerschmidt says. “Being in a situation where you can have a really productive conversation with the director, that is so rare and so important.”

Erik Messerschmidt films Mank

Photo by Gisele Schmidt-Oldman

The duo spoke to Queue about what makes their partnership work.

Erik, how would you describe working with David? What makes the experience unique?

Erik Messerschmidt: Well, it’s amazing. David is precise but collaborative.

David Fincher: You’re not saying that because you happen to be on Zoom with me?

EM: No! David is unique as someone who watches everything. Some people might accuse him of being obsessive. I would never use that word. I would use the words “precise” and “considerate,” actually. He’s looking at the performance. He’s looking for the position of the microphone. He’s looking at the set dressing and the background. He’s looking at the lighting we’ve done and how all that stuff is forming together to make the shot, and then how all the shots are forming to make the scene.

It’s very rare as a cinematographer to have the opportunity to pull a director aside and explain the problem you’re having creatively and at the same time explain the problem you’re having technically, and then to have an ally in that conversation. David is very good at saying, “I understand. I can see how that’s a problem. Let me adjust this position here, I’ll change the timing here.” When I’m not in that environment, I’m like, Man, where is David? This would be so easy if he were here.

DF: I’ve heard my sets described as operating theaters, or like being on a space station: Pencils down, I need everybody focused. But there’s a cadre of people whom I don’t ever want to be aware of the time of day or of how much film we’ve shot — and that’s the actors. A lot of people feel that the time between takes is chit-chat time, and I’m like, If the actors are in front of the camera, I don’t want to hear from anybody else, unless you’ve got something to let me know. It’s not to make it unpleasant, it’s just to keep everyone focused on the fact that we’re here to photograph actors and we’re here to photograph them acting.

Amanda Seyfried on set

Photo by Nikolai Loveikis

What was most exciting for you about working completely in black and white?

EM: Honestly, I was nervous about it before we really looked at it. I had shot with that RED 8K Helium Monochrome camera a little bit before. I knew it was spectacular, but I had this hunch that maybe we would also want the color information so that we could grab those colors, grab the grade, change the tone, and have a little bit more freedom.

We shot the black-and-white camera against the color camera in order to evaluate that empirically. We screened the footage, and there was no question. It was such a staggering difference. There were other advantages that were unforeseen. The camera’s so much faster, which helped us because we were doing all this deep-focus photography and we needed more lights. It just had this silvery, gelatin-print depth to it that you do not get when you desaturate color.

DF: The trick in this film is to give a nice formal hug to what cinematographer Gregg Toland brought to his era — not even to Citizen Kane specifically, but to the way people think about black-and-white photography. It’s funny because people may say, “Mank doesn’t really share a sense of Citizen Kane.” Remember, part of what makes Kane feel the way it does is that every character exists in a tomb. Every place that movie goes to, it’s this dark, oppressive mausoleum, with shafts of light. Our story takes place in this stucco bungalow with squeaky wood floors and dust and cow shit right outside the front door. There’s no direct corollary with Kane. You can make yourself crazy trying to apply something to a story when the story is rejecting it. You can’t get too intractable about superimposing shafts of sunlight where they don’t make any sense.

I like that period immediately after the rehearsal when you get to formulate your dreams.

Erik Messerschmidt

You shot day for night in this scene where Mank and Marion Davies take a stroll around the Hearst Castle grounds. Take us through that.

DF: Erik was working on a television show for Ridley Scott, Raised by Wolves, and he sent me some stills of the day for night that he had done on that, and they were really beautiful. It’s not such a magic trick. This is how they used to do it in the days of Louis B. Mayer. “A rock is a rock, a tree is a tree. Shoot it in Griffith Park.” They shot day for night, and they did it for a reason: because it’s a hell of a lot cheaper.

EM: The French call it “American night.”

DF: They do? That is so passive-aggressive.

EM: I loved it, I thought it was so much fun. I mean, I haven’t slept more poorly before a shoot than I did those three or four days. I was so scared that the sun wasn’t going to come out. We were definitely rolling the dice.

DF: As we were scouting the Huntington, we kept talking about where the sun needed to be. If you’re shooting in sunlight, what you’re having a discussion about is hours. You’re discussing what time of day and where craft services is going to have to be relocated so that it isn’t seen. We did that a lot. Our discussions, which were really about how silvery things would be, ended up being about how we have between 11:15 and 11:28 a.m. to get the shot and then we’ve got to move around to a new setup.

EM: Yeah, we were there, like, O.K., synchronize! Reset, quick!

DF: There were a lot of times when we would say, We can’t get this now. We’re going to have to move on, we’ll come back to it tomorrow. If the sun’s in the wrong place, you can’t get the shot.

The light was so intense on the actors that special contacts were made for Gary Oldman and Amanda Seyfried. True?

EM: Tinted contact lenses, yes. We shot a test in prep, and Gary was streaming tears, “I don’t know guys...” You underexpose the camera so much that you put a lot of front-light on the actors, more than you normally would if you were shooting a day scene. We were looking at the monitor thinking,Oh, it looks great! This totally works. This is going to be perfect...

DF: ...But why is he squinting like a mole?

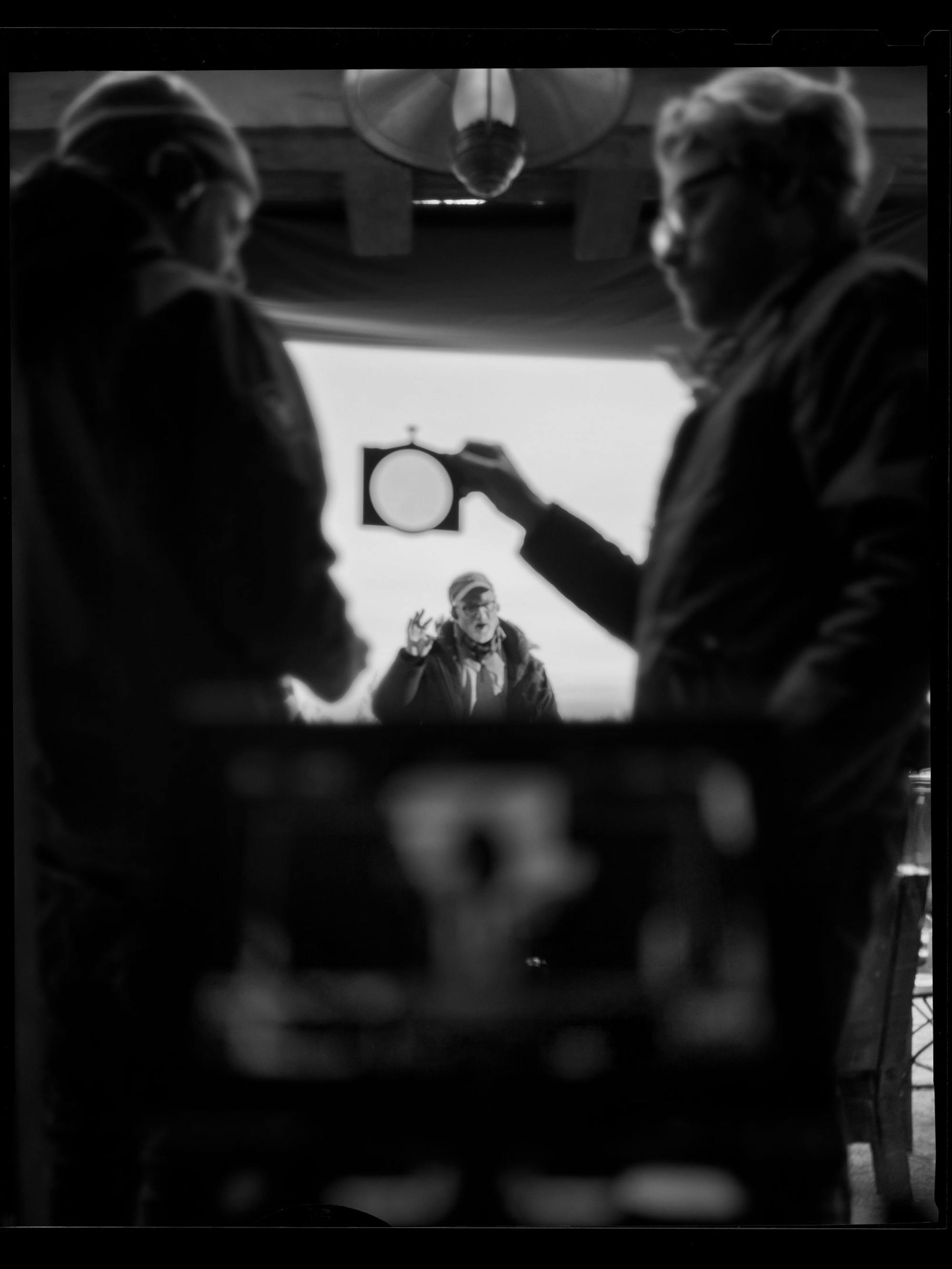

David Fincher and Erik Messerschmidt discuss lenses

Photo by Miles Crist

Is there a favorite moment of the day when you’re working?

EM: I like that period immediately after the rehearsal when you get to formulate your dreams. Then you spend the rest of the day crushing them. I like that process of figuring it out, watching David block with the actors and watching them work the scene out, and then talking with him about how we’re going to cover it or how it’s going to be lit. That’s really where the scene emerges: in that short period between the rehearsal and the first shot you do in the scene.

DF: Even when you have four days or five days, scenes like Gary wandering around a 54-foot table with 28 guests are the scenes that start to feel like an elephant is sitting on your chest. When you’re trying to figure out how to position two cameras for two people to meander through a garden, you don’t necessarily have faith that it’s going to happen like falling off a ladder — but those scenes are easy compared to shooting in a room, doing a scene that has eight speaking parts in it and 20 people that all have to be integrated. For an 11-page dialogue scene where Gary Oldman has to make three laps around a 54-foot table, even when you get the master you’re still sweating, Oh my God, I have another two days of this madness.

EM: You’re going through your notebook, and it’s like, Ugh, there are so many more shots to do. In those scenes, the favorite part of the day is the scotch at home.