Spike Lee’s Da 5 Bloods and Aaron Sorkin’s The Trial of the Chicago 7 remind us that we’ve been here before.

It feels like 2020 has been the most spiritually exhausting year in recent memory. Every morning arrives with some harrowing, this-just-in headline that threatens to push our collective sense of sanity to the breaking point. It’s impossible to keep up, nevermind keep your balance.

The constant churn may make us feel as if we’re living through a uniquely turbulent moment in American history, but the truth is, we are not. We’ve been here before. Or, at least, someplace very much like here. And it wasn’t that long ago. I’m referring to 1968 — a year in which the tectonic plates of our culture shifted constantly under our feet.

In the lead-up to that annus horribilis 52 years ago, there was reason for optimism. In 1967, the Summer of Love ushered in an Aquarian sense of rebirth. Thurgood Marshall became the first Black American confirmed to a seat on the Supreme Court bench. The Lunar Orbiter 3 brought America one step closer to President John F. Kennedy’s promise of landing a man on the moon by the end of the decade.

Still, as 1968 kicked off, doom was in the ether.

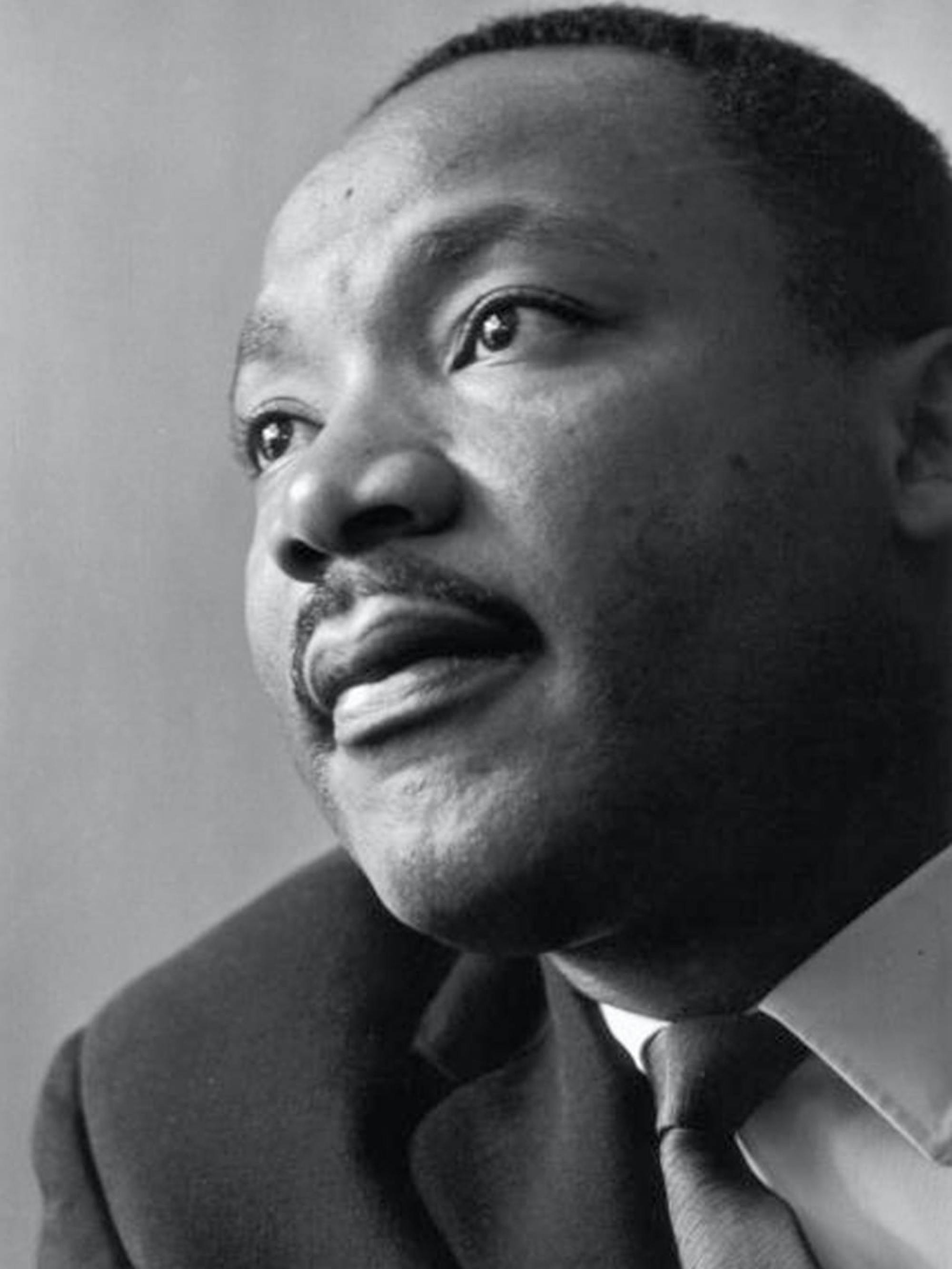

In January, the Tet Offensive became a bloody harbinger that the war half a world away would not — and could not — be won. In March, the My Lai massacre saw U.S. troops slaughter hundreds of Vietnamese civilians. The same month, President Lyndon Johnson announced that he would not seek another term in office. In April, Martin Luther King Jr. was slain on the balcony of his Memphis motel room. In June, presidential hopeful Robert F. Kennedy was gunned down as he was leaving the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles. In August, anti-war protesters violently clashed with club-wielding police officers outside of the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. And in November, Richard Milhous Nixon won his bid to become the 37th president of the United States. In the moment, it was difficult to make sense of this surreal and seismic swirl of events, but historians would look back on 1968 as “The Year That Rocked the World.”

Martin Luther King Jr.

Photo by Reg Lancaster / Express / Getty Images

Robert F. Kennedy

Photo by Michael Mauney / the Life Picture Collection via Getty Images

No wonder there’s a sense of déjà vu between 1968 and 2020. Political pundits and pop-culture soothsayers have certainly cited the psychic link between the bad vibes of then and those of now. But it’s the artists in our society who possess the real sixth sense for reflecting our collective anxieties back at us. The most attuned among them act as human divining rods, sensing the troubles underground before they bubble up to the surface.

Two notable films of 2020 exhume the past as a reflection of our present in this way: Spike Lee’s Da 5 Bloods zaps us back to the height of the Vietnam War, imploring us to grapple with the shameful inequity of Black soldiers forced to fight in yet another white man’s war; Aaron Sorkin’s incendiary courtroom drama The Trial of the Chicago 7 reaches back to the turbulent summer of 1968 to resurrect a stranger-than-fiction moment in U.S. history. Both offer a fascinating dialogue between one tumultuous era and another.

Lee opens Da 5 Bloods with knockout force. A montage of news clips connects the escalating war in Southeast Asia and the escalating war at home between Black and white Americans. The film continues to cut between the present and the past as the four Black Vietnam War veterans at its center reunite to recover a buried treasure and the body of their fallen leader. The narrative time travel touches off ideological landmines from both periods: red MAGA hats and the Black Lives Matter movement in the now; Martin Luther King’s murder and Black Power then. It’s a movie that’s partially set in the 60s but finds particular resonance in 2020, when race is on the collective American mind in a way that it hasn’t been for some time. Injustice, Lee’s saying, is timeless. It reappears in different guises.

The same wisdom resounds in Sorkin’s The Trial of the Chicago 7. The film traces the dubious legal case brought by Nixon’s attorney general against the activists and agitators who demonstrated at the 1968 D.N.C. The defendants were marching to end the war in Vietnam, but when the billy clubs start swinging onscreen, it’s impossible to miss the sickening parallels to the last four years. The chant keeps rising: “The whole world is watching! The whole world is watching!” Those words couldn’t feel more urgent in an age when brutal encounters are uploaded for all to witness. Sorkin reminds us what it costs to stand up to a government that has forgotten its promise to be of the people, by the people, and for the people. It’s those insistent parallels that give the film its bare-knuckle power.

Delroy Lindo, Clarke Peters, Chadwick Boseman, Isiah Whitlock Jr., and Norm Lewis of Da 5 Bloods

Image Courtesy of Netflix

Police and demonstrators face off in The Trial of the Chicago 7

Image Courtesy of Netflix

If America was so clearly a different-yet-similar place in 1968, then so was Hollywood. It’s tempting to look at the major studios during the tail end of the decade as slow to catch up to the changes that were occurring in the culture. Yet around the nation, movie theater marquees were neon-bright signs of change.

That change would end up announcing itself most clearly on the evening of April 10, 1968, when the 40th Academy Awards were held at the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium. That year, the five nominees in the horserace for Best Picture represented an uneasy mix of old and new. The ceremony determined an industry sea change. Representing Old Hollywood was Doctor Dolittle, a square, big-ticket extravaganza starring Rex Harrison as a veterinarian who can talk to animals. Stacked on the opposing side were the night’s four other nominees: Bonnie and Clyde, The Graduate, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, and In the Heat of the Night.

Aside from Doctor Dolittle, each of these films not only reflected the changing values in the country, they embraced them.Although set against the backdrop of the Depression, Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde was inspired by the French New Wave, and virtually jumped off the screen as an anti-establishment allegory for the fed-up 60s’ counterculture. Meanwhile, Mike Nichols’s The Graduate, which starred Dustin Hoffman as an aimless twentysomething bucking against white-collar responsibility (“One word: plastics”), was revelatory for young moviegoers rebuffing their Eisenhower-era parents.

Faye Dunaway and Warren Beatty in Bonnie and Clyde

Photo by Michael Ochs Archives / Getty Images

Anne Bancroft and Dustin Hoffman in The Graduate

Photo by Sunset Boulevard / Corbis via Getty Images

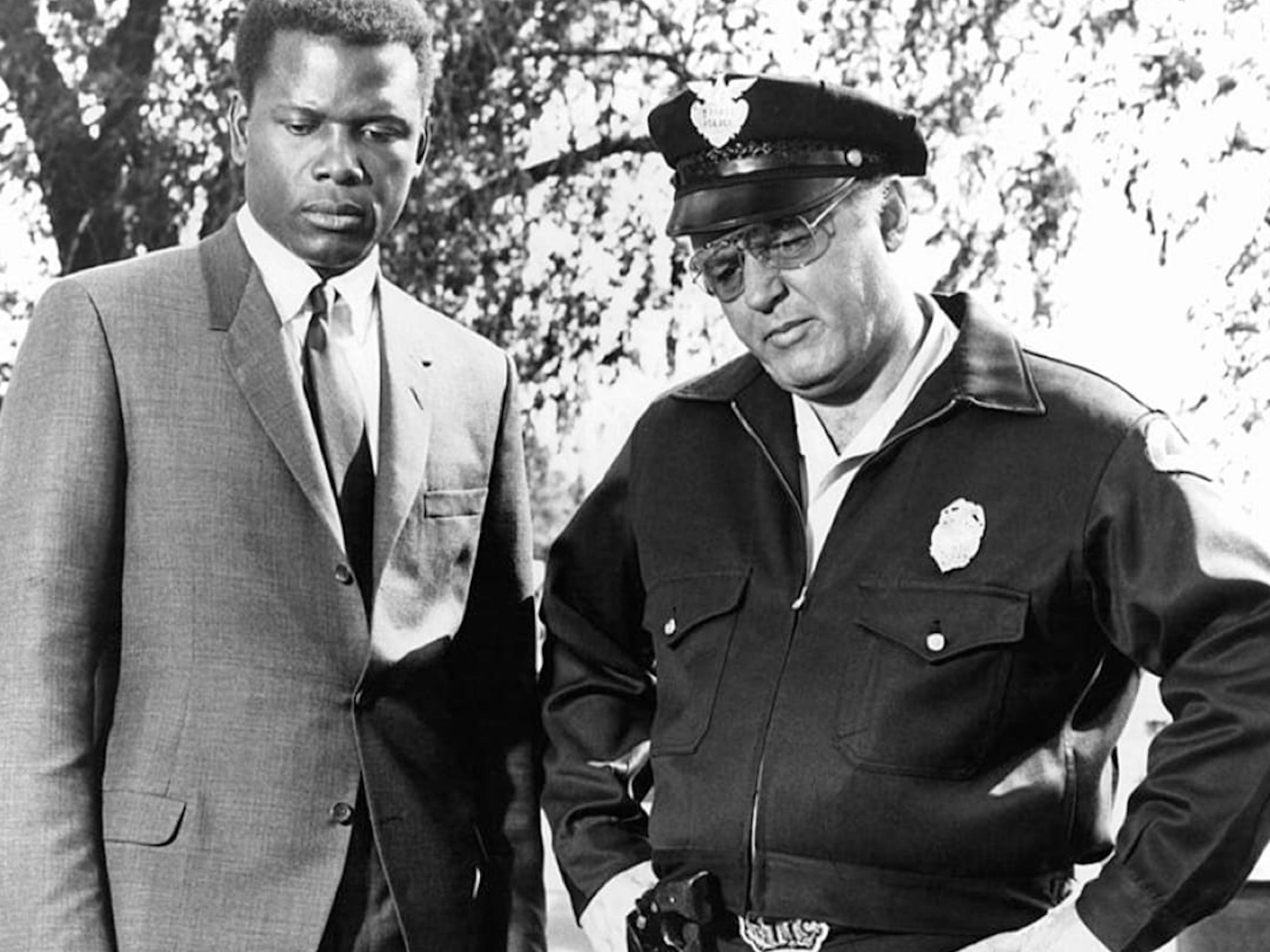

Then there were the two films that starred one of the most popular Black actors of the decade: Sidney Poitier. Both tackled race head-on, albeit with different degrees of ferocity. Stanley Kramer’s Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner told the story of a young interracial couple — Poitier and Katharine Houghton — who must break the news of their engagement to Houghton’s character’s liberal white parents, played by Spencer Tracy and Katharine Hepburn. As Tracy and Hepburn wrestled with prejudices onscreen (admittedly with kid gloves), middle-aged ticket buyers couldn’t help but do the same.

On the other hand, there was Norman Jewison’s In the Heat of the Night — a far more provocative film, about a Black Philadelphia police detective (Poitier) and a bigoted, good ol’ boy sheriff (Rod Steiger) investigating a murder in a racially hostile Mississippi backwater. In its most explosive moment, a white man slaps Poitier’s character across the face. Poitier has the audacity to slap him back. In theaters across the country, that blow, delivered in the midst of the struggle for civil rights, resounded like a thunderclap. In the end, In the Heat of the Night walked off with the award for Best Picture. It seemed that Hollywood had caught up to the zeitgeist at last.

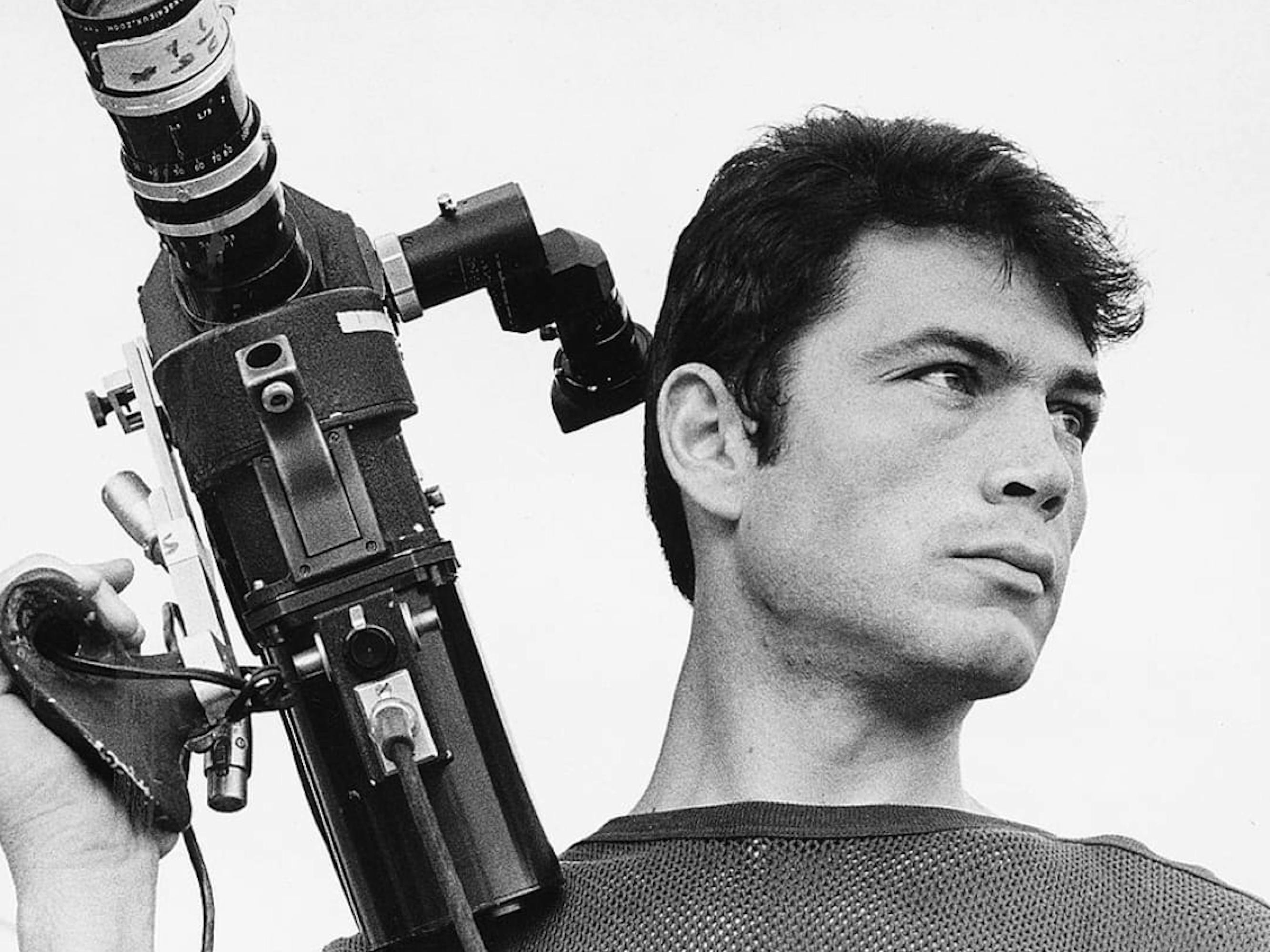

Cinema’s impact on the troubled soul of America wasn’t just confined to the black-tie environment of the Academy Awards. Several other films from both the major studios and the indies on Poverty Row were grappling with what was going on in the streets and in the margins. Cinematographer-turned-director Haskell Wexler brought his camera to Chicago for the 1968 D.N.C., where he shot his quasi-documentary Medium Cool and bore witness to the same skull-cracking that Sorkin chronicles in The Trial of the Chicago 7. Barry Shear’s Wild in the Streets took a cue from such popular, fight-the-power Roger Corman biker pictures as The Wild Angels, and offered a psychedelic vision of what America might look like if the rock ’n’ roll generation overthrew the system. The implicit message in all of these films was the same: America was changing, and you could either change with it or be left behind.

And then there was a little, $114,000 black-and-white movie that seemed to come out of nowhere — or just outside Pittsburgh. George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead looked like some guts-a-poppin’ gorefest you’d find on the bottom half of a 42nd Street grindhouse double bill, but savvy filmgoers interpreted that beneath the zombie mayhem was a fairly subversive allegory about race in our country. The Black lead (played by Duane Jones) is martyred in the film’s final moment; in the end, the most terrifying monsters are white men armed with rifles.

Sidney Poitier, Katharine Houghton, and Spencer Tracy in Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner

Photo by John Springer Collection / Corbis / Corbis via Getty Images

Sidney Poitier and Rod Steiger in In the Heat of the Night

Photo by United Artists / Getty Images

When 1968 finally drew to a close, Hollywood still wasn’t done with it. One of the keenest films about that year didn’t actually arrive in theaters until 1975. Hal Ashby’s Shampoo is set in 1968, orienting itself around election day — dark skies on the political horizon. Warren Beatty stars as George Roundy, a charismatic, bed-hopping hairdresser catering to the wives, mistresses, and even teenage daughters of the Beverly Hills Republican elite. The movie is a farcical satire about narcissism, sexual liberation, and the insatiable itch of romantic restlessness. But by setting it in that fateful year, Ashby also signals something else, something that only comes with the clarity of hindsight. Beneath the film’s lighthearted veneer is the pervasive sense that an era is ending, that a moral reckoning is coming. A new conservatism is on the march, and with it, even more political division.

The same year that Shampoo hit theaters, the war in Vietnam finally reached its bitter end. Throughout the 70s and 80s, directors continued to try to make sense of the senseless conflict, picking at wounds that had not yet healed. Hal Ashby’s Coming Home, Michael Cimino’s The Deer Hunter, Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now, Oliver Stone’s Platoon, Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket, and Brian De Palma’s Casualties of War all attempted to come to terms with a trauma defined by 1968.

Robert Forster in Medium Cool

Photo by Silver Screen Collection / Hulton Archive / Getty Images

Julie Christie and Warren Beatty in Shampoo

Photo by Silver Screen Collection / Getty Images

Flash forward to 2020 and movies once again offer us opportunities to know more about ourselves, one another, and the times we live in. With Da 5 Bloods and The Trial of the Chicago 7, Lee and Sorkin ask some of the same fundamental questions we were asking five decades ago. They prove (as if any proof were needed at this point) that they are storytellers who understand that the past isn’t the past at all; it’s prologue. In so doing, they continue the same cinematic lineage of empathy and engagement that broke through the chaos of 1968.

If the particulars of the here and now are different, the rudiments are not. We’re still trying to make sense of our third-rail times. These films hold up a mirror. The reflection may not be pretty, but if we look, it offers lessons.